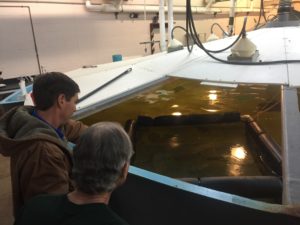

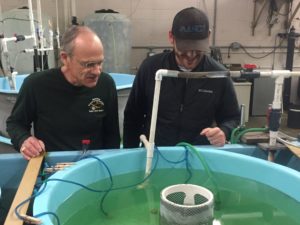

Master’s student, Grayson Clark, and Research Associate Brian Ray spent 2 days in Corpus Christi this week, at the TPWD CCA Marine Development Center, setting up an experimental system to test larval flounder live feed enrichments as part of the SRAC grant the Aquacultural Research and Teaching Facility was awarded last fall. See the original story here.

They plan for the system to be stocked with new hatched larval flounder from TPWD Sea Center Texas on January 21. Dr. Ivonne Blandon is working with ARTF personnel to run this first phase of the work in Corpus. Dr. Blandon, who works as Natural Resource Specialist for Texas Parks & Wildlife Department Coastal Hatcheries, is a recent WFSC graduate under Dr. Gelwick. A similar system will be set up at the ARTF and run follow up studies with flounder and other estuarine species (red drum and spotted seatrout).

To see more about what the Aquacultural Research and Teaching Facility entails, head over to the ARTF Facility‘s page. For information on how to Give to the Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences Department to support our research and opportunities, visit our Giving page.

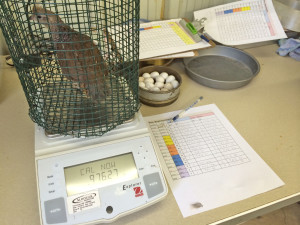

Southern flounder are “floundering” as wild population densities decline. One of the big three sportfish in Texas, along with redfish and spotted seatrout, southern flounder are a sought after gamefish of commercial and recreational importance. Due to overharvest, accidental bycatch, water temperature rise and other factors, the flounder numbers are declining in Texas waterways. Along with Texas Parks and Wildlife, Texas A&M University’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries’ Dr. Todd Sink and graduate research assistant Elizabeth Silvy have developed a methodology that may aid stock enhancement programs that promote the flounder fishery.

Southern flounder are “floundering” as wild population densities decline. One of the big three sportfish in Texas, along with redfish and spotted seatrout, southern flounder are a sought after gamefish of commercial and recreational importance. Due to overharvest, accidental bycatch, water temperature rise and other factors, the flounder numbers are declining in Texas waterways. Along with Texas Parks and Wildlife, Texas A&M University’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries’ Dr. Todd Sink and graduate research assistant Elizabeth Silvy have developed a methodology that may aid stock enhancement programs that promote the flounder fishery. in the wild, and that larval flounder are temperature dependent when it comes time to form gonads. If temperatures are too high or too low, a majority of the offspring produced will be male. This has been proven true in the wild as well as in stock enhancement programs currently run by TPWD. To produce a hearty wild flounder stock, or even promote hatchery numbers, a majority of the offspring must be female, as one male can mate with a hundred females.

in the wild, and that larval flounder are temperature dependent when it comes time to form gonads. If temperatures are too high or too low, a majority of the offspring produced will be male. This has been proven true in the wild as well as in stock enhancement programs currently run by TPWD. To produce a hearty wild flounder stock, or even promote hatchery numbers, a majority of the offspring must be female, as one male can mate with a hundred females. ale are created. These female/male flounder can then be bred back to wild females collected from TPWD’s stock enhancement programs to produce all female progeny to be release in the wild.

ale are created. These female/male flounder can then be bred back to wild females collected from TPWD’s stock enhancement programs to produce all female progeny to be release in the wild. male reproductive organs in a genetically female fish. These fish will never be released into the wild; instead they will be kept as broodstock to breed with female flounder collected from the wild to maintain genetic diversity. These fish will only produce genetically and physically female flounder that have not been altered in any way. These offspring can then be released into the wild to supplement wild populations.

male reproductive organs in a genetically female fish. These fish will never be released into the wild; instead they will be kept as broodstock to breed with female flounder collected from the wild to maintain genetic diversity. These fish will only produce genetically and physically female flounder that have not been altered in any way. These offspring can then be released into the wild to supplement wild populations.