By: Paul Schattenberg

UVALDE — As part of an effort to understand the reasons behind the decline in wild quail populations, researchers from Texas A&M AgriLife Research have studied whether the continued increase in numbers and distribution of wild pigs, commonly referred to as feral hogs, may be a contributing factor.

According to data from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, within the South Texas Plains ecoregion bobwhite populations have been consistently low since the mid-1990s and to date have shown few signs of recovery despite land-management efforts to improve populations.

“Wild pigs are known to eat the eggs of ground-nesting birds, but whether they impact wild quail populations is unknown,” said Dr. Susan Cooper, AgriLife Research natural resource ecologist at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in Uvalde, who served as lead study investigator.

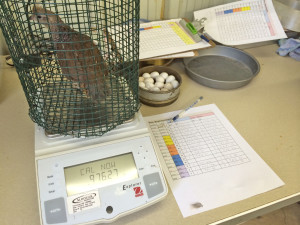

Wild pigs, commonly known as feral hogs, are known to predate quail nests and eat their eggs. (Texas A&M AgriLife Research photo)

Cooper said nest predation studies using artificial nests baited with quail or chicken eggs, as well as in-vivo field experience, showed wild pigs invade the nests of bobwhite quail to consume their eggs.

“Our study was able to demonstrate that on semi-arid rangeland, differences in habitat use and selection by Northern bobwhites and wild pigs should limit interaction between the species,” she said.

However, she noted, the study also showed there are still opportunities for quail nest depredation by wild pigs due to riparian areas providing access to drier upland areas.

By comparing the habitat use of quail and wild pigs, Cooper and her fellow scientists hoped to provide guidance on the rangeland sites where control of the feral swine might have the greatest positive impact on northern bobwhite quail populations. To achieve this, the scientists solicited the cooperation of the owner of an 84,000-acre-plus, low-fenced ranch in Zavala County used for game production and cattle grazing.

“We combined GPS data on the movements of 40 feral hogs collected in a prior study, with 10 years of spring call-count data available for quail on the ranch and three nearby properties,” Cooper said.

To get information on their habitat preferences, wild pigs were trapped and outfitted with a GPS collar. (Texas A&M AgriLife research photo)

The call counts were made annually from 2004 to 2014 during mating season — mid-April through May. Quail rooster calls were recorded at 10 call stations spaced equidistantly along about a 10-mile route on each ranch. Information on habitat use and selection by wild pigs was based on two years of data collected on the main study ranch using GPS-collared wild pigs whose movements were recorded every 15 minutes.

“Through combining these studies, our goal was to identify habitats within South Texas rangeland in which wild pigs were most likely to overlap in distribution with the bobwhites,” Cooper said.

Cooper said the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resource Conservation Service had determined the soil types of the study ranch were predominantly clays and clay-loams with a small area of deep sandy soil..

“The most characteristic woody plant on the ranches was honey mesquite, which was growing in combination with pricklypear cactus and a diverse array of drought-tolerant shrubs,” Cooper said. “Riparian areas were predominantly narrow bands of dense shrubs and mesquite trees along drainage areas. In contrast, the sandy areas provided an open prairie habitat.”

Research results showed bobwhites on the study ranch strongly preferred the area with deep sandy soil. In contrast, wild pigs favored areas underlain by clay soils, and especially riparian areas of that soil type. On the other three ranches, which lacked the sandy soils, the bobwhites showed no clear preference for any particular ecological site.

“There is a thermoregulatory requirement for wild pigs to stay near riparian areas because, like their domesticated relatives, they have no sweat glands and the water and cool ground in these locations help regulate their body temperature,” Cooper said.

She said in spring and summer, when quail have nests on the ground that are vulnerable to predation by mammals, feral hogs were typically in the vicinity of water and riparian habitats that make unsuitable nesting habitat for quail.

The study showed the greatest overlap in habitat selection by wild pigs and bobwhites occurred early in the quail-breeding season when the swine were more often located in the clay-loam areas.

“These shrub dominated sites, while not highly preferred by bobwhites as long-term habitats, are used extensively for nesting,” she said. “However, most locations of wild pigs within clay-loam areas were not in native vegetation but fallow fields too sparsely vegetated to be of use to nesting quails. Thus chances of the swine locating quail nests were less than may be expected.”

However, Cooper noted, the network of creeks and drainages allowed hogs to infiltrate into drier rangeland areas where quail do nest.

“The special distribution of creeks and drainages may provide these opportunistic omnivores with travel routes into the drier upland areas preferred by bobwhites as a habitat for establishing their nests,” she said.