By: Paul Schattenberg

UVALDE – In an effort to discover find what’s causing the decline of Texas wild quail populations, Texas A&M AgriLife Research scientists investigated whether regular ingestion of low levels of aflatoxins by bobwhite and scaled quail may impacttheir ability to reproduce.

VIDEO: Quail and Afaltoxin Study: https://youtu.be/KV1r1ZONWDE

The study on aflatoxin ingestion by quail addressed what might occur if quail consumed grain-based feed infected by these fungal toxins. The study’s purpose was to see if repeated consumption of low levels aflotoxins might affect quail reproduction. (Texas A&M AgriLife Research photo)

“In trying to identify reasons behind the decline in quail populations in Texas, we determined it would be worthwhile to study whether aflatoxins, which are fungal toxins that contaminate grain, might be a concern,” said Dr. Susan Cooper, AgriLife Research wildlife ecologist at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in Uvalde.

“We wondered whether eating grain-based feed supplements for wildlife, especially deer corn, might possibly expose quail to chronic low levels of aflatoxin poisoning, thereby affecting their reproductive ability.”

Cooper was helped in the study by research assistant Shane Sieckenius and research technician Andrea Silva, both of AgriLife Research in Uvalde.

Cooper said previous research has shown acute dosages of 100 parts per billion of aflatoxin in poultry could cause liver damage or dysfunction, leading to ill health as well as reduced egg production and hatchability.

In wild quail, such effects would result in a decrease in reproductive output and reduction in quail population, she said.

“We knew that experimental doses of even small amounts of aflatoxins may cause liver damage and immunosuppression,” Cooper explained. “So the objective of this study was to determine whether consumption of aflatoxins in feed at those levels likely to be encountered as a result of wild quail eating supplemental feed provided for quail, deer or livestock, would result in a reduction in their reproductive output.”

The researchers conducted feeding trials using 30 northern bobwhites and 30 scaled quail housed in breeding pairs. They initially conducted free-choice trials on three replicate pairs of each type of quail to determine if they could detect the presence of aflatoxin in their feed. The birds could not detect and avoid aflatoxins.

Then for 25 weeks, encompassing the breeding season of March through August, the researchers divided the remaining quail into four groups of three pairs of each species. These 12 pairs of caged northern bobwhites and 12 pairs of scaled quail were fed diets that included twice weekly feedings of 20 grams of corn. The corn had either 0, 25, 50 or 100 parts per billion of aflatoxin B1 added to it prior to consumption by the quail.

“These amounts of aflatoxin — 25, 50 and 100 parts per billion — represented the recommended maximum levels for bird feed and legal limits for wildlife and livestock feed respectively,” Cooper said. “And the feeding schedule mimicked what would occur with wild quail periodically visiting a source of supplemental feed.”

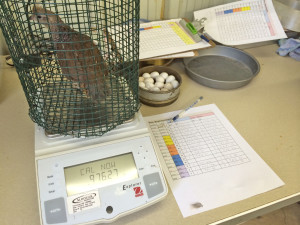

Quail were weighed monthly to see if there was any weight change due to the consumption of grain-based feed with low-level amounts of aflatoxion. (Texas A&M AgriLife Research photo)

The researchers measured any changes in reproductive output and quail health over the six-month breeding period. Reproductive output was measured in terms of number of eggs produced per week as well as the weight of the eggs and their yolks. Health changes were measured by the amount of food consumed by the quail on a weekly basis and by any reduction in weight as measured on a monthly basis.

“We had to extract the birds from the pens using butterfly nets, then put them into a small enclosed cage area to weigh them,” said Sieckenius, who also prepared the corn for adding the aflatoxin. “We collected eggs daily and hard-boiled the eggs collected on the last week of each month to extract the yolks so we could accurately measure their weight.”

Cooper said the results of the study showed intermittent consumption of aflatoxin-contaminated feed had no measurable effect on the body weight, feed consumption and visible health of either species of quail.

“The reproductive output, measured by number of eggs produced, egg weight and yolk weight, was also unaffected,” she said. “Thus, in the short term, it appears that chronic low-level exposure to aflatoxins has no measurable deleterious effects on the health and productivity of quail.”

Cooper said as a result of the study it was possible to conclude that aflatoxins in supplemental feed are unlikely to be a factor contributing to the long-term population decline of northern bobwhite and scaled quail through reduced health or egg production. However, she cautioned that feed should be kept dry to avoid potential contamination with higher levels of aflatoxin that may be harmful.

”This project also does not address any long-term effects of aflatoxin consumption that may become evident when wild quail are exposed to nutritional or environmental stresses,” she said.