Northern Bobwhites (Colinus virginianus) are probably the most well-known species of quail in Texas. Their distinct call, which announces their name and attraction by hunters and photographers alike, make the Northern Bobwhite a sought after upland gamebird species. However, in Texas, bobwhites can be found statewide, with minor populations occurring in the Trans-Pecos eco-region. Lack of adequate rainfall is thought to limit the quail movement further west. The bobwhite has been found in all 10 eco-regions of Texas but their actual populations in each area fluctuate based on a number of factors, including climatic and habitat conditions. Bobwhite prefer habitat that includes bare ground, herbaceous cover, and woody cover. Bare ground allows for the foraging of seeds, herbaceous cover provides overhead concealment and loafing cover for resting, and woody cover protects against predators and the Texas heat. Bobwhites seem to prefer more open ground and less grass cover in areas of high precipitation while favoring the opposite where lower precipitation occurs.

Vocalizations

Known for their calls, bobwhites are very social and remain with a covey, or group of 6-25 quail, for the duration of their lives. A bobwhite uses several different calls but has a specific use for each one, including attracting a mate (“ah, bob-white”), organizing a covey (“koi-lee” or “hoyee”), alerting for danger (“toil-ick, ick, ick”), and distress (“t-s-I-e-u, t-s-I-e-u, t-s-I-e-u”). Males, or cocks, issue the breeding call around March through June, but have been heard during the nonbreeding season as well.

Physical Attributes

Like other New World species, the Northern bobwhite has a shorter neck, tail and wings. They exhibit a distinct color pattern of black, white and brown, with males displaying a white stripe near the eyes and throat and females showing a lighter brown brow stripe and throat. Both sexes have a tufted crest on their heads and use this feature to attract a mate or in the case of males, showcase masculinity around other males. Because of their short wings, Northern bobwhite prefer to spend more time on the ground and only tend to take flight when disturbed, but the flight distance is short.

Nesting and Incubation

In preparation for the breeding season, coveys in Texas will breakup around February or March and form individual pairs by mid-March and April. To attract a mate, males offer lateral displays and bowing while females prefer wing quivering and presentation. Recent research suggests that bobwhites are polygamous, or mate with several partners. The nesting season in Texas lasts from mid-April to early October, with peaks during the summer months. This season is heavily affected by weather, where intense heat and drought shorten nesting while extended rainfall and cooler weather lengthen it. Nests are prepared on the ground with the necessary amount of cover to protect all sides from predators. Bunchgrasses provide ample cover and consist of bluestems, threeawns, balsamscales, and lovegrasses. Depending on the eco-region, forbs, shrubs, sand sagebrush, and prickly pear cactus are the preferred nesting cover. Female hens then lay their eggs within 1-7 days of nest completion until the entire clutch is delivered, usually about 12-15 eggs. Quail eggs are white and oval shaped, like a guitar pick, and slightly larger than a silver dollar. The females then incubate the eggs for approximately 23 days. The survival rate of the nest varies due to depredation, or predator attacks, abandonment, human activities (farming, interference), and weather. Once hatched, bobwhite chicks are brooded by the female until adequate down, or fur, appears, usually around 3 to 5 weeks. These juvenile bobwhites are precocial, or capable of moving independently but still require parental care, and become mature adults by 15 weeks old.

Habitat and Diet

The Northern bobwhite is granivorous, or seed eating, and prefers to consume seeds found on forbs and grasses during the fall and winter months. Important forbs include Engelmann daisy, western ragweed, croton, sunflower, and legumes such as snoutbeans and bundleflowers. Hard-seeded grasses such as bristlegrasses, panicums, and paspalums are also important. They eat green vegetation, mast (seeds and fruit from shrubs), and insects throughout the spring and summer months, which aids in meeting the female’s nutritional needs during the breeding season. Mast producing shrubs include agarito, chittam, mesquite, and hackberry. Insects such as grasshoppers, beetles, crickets, ants, termites, and spiders are favorites of bobwhites as they are both a source of protein and preformed water.

Predation and Other Mortality Factors

The average lifespan of the bobwhite is about 6 months and under ideal conditions, bobwhites can survive up to five years in the wild. All of the influences that lead to bobwhite declines must be considered to completely understand the roles played in the alarming decline of quail in Texas. First, the high-mortality rate during nesting is due to changes in habitat conditions which can be influenced by a myriad of both direct and indirect factors. Direct factors can include habitat fragmentation, conversion of native pastures into introduced grasses, poor grazing management, agricultural cultivation and nest depredation by coyotes, raccoons, striped skunks, and snakes. Indirect factors are primarily related to climatic conditions such as temperature and precipitation.

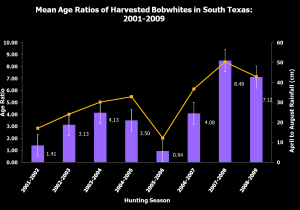

(Click to Enlarge) This graph shows the relationship between rainfall and adult-to-juvenile ratios of bobwhite quail in south Texas. The data represented suggests that rainfall can be an indicator of bobwhite quail production in south Texas. For additional background on this data, consult Tri et al. (2013) within the Journal of Wildlife Management Volume 77, Issue 3, pages 579-586.)

Second, variable influences of weather (snow, hurricanes, drought, heat waves, wind, flooding) and disease (eye worm, viral/bacterial/mycotic/protozoan diseases) are key components of quail survival. Once the chicks grow new predators arrive. Red imported fire ants, small mammals, and avian predators (northern harrier, Cooper’s hawk, and large owls) all pose significant threats to the survival of bobwhites. Last, the human influence of harvest is considered to be somewhat additive to the other factors that lead to bobwhite mortality, thus increasing the mortality rates of bobwhites across the population. However, bobwhites can be harvested at sustainable levels which range between 30 to 40 percent of the annual estimated population.

Conservation and Management

The loss of quail habitat in Texas is significant, and with over 90% of the state privately owned, landowners are the key to conservation. The conversion of prairies, savanna, shrubland and woodlands to commercial and residential uses, cropland cultivation, and overgrazing have all greatly decreased the amount of lands viewed as sustainable for bobwhites. Recognition of and a consolidated effort towards a positive change by private landowners, commercial industries and wildlife managers is required before the Northern bobwhite can begin to see an increase in population. Even small changes now can lead to larger changes in the future for the quail of Texas.

Citations:

Dr. Dale Rollins and the Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch, Roby, Texas

Hernandez, F., and M. J. Peterson. 2007. Northern bobwhite ecology and life history. Pages 40-64 in L. A. Brennan, editor, Texas Quails: Ecology and Management. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Tri, A. N., Sands, J. P., Buelow, M.C., Williford, D., Wehland, E. M., Larson, J. A., Brazil, K. A., Hardin, J. B., Hernandez, F. and Brennan, L. A. 2012. Impacts of weather on northern bobwhite sex ratios, body mass, and annual production in south Texas. Journal of Wildlife Management 77:579-586.

Quail Associates Program, Richard M. Kleberg, Jr. Center for Quail Research, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute

Map: Sauer, J. R., J. E. Hines, J. E. Fallon, K. L. Pardieck, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W. A. Link. 2012. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2011. Version 07.03.2013 USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD

Videos:

Out On The Land – Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch (Part 1)

Out On The Land – Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch (Part 2)

Suggested Readings:

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Bookstore

Upland Game Birds

NR-001 Texas Quails: Ecology and Management

NR-002 Beef, Brush, and Bobwhites: Quail Management in Cattle Country

NR-003 On Bobwhites

B-6172 Habitat Monitoring for Quail on Texas Rangelands

B-6173 Counting Quail

E-98 Integrating Deer, Quail and Turkey Habitat

ESP-419 Feral Hogs’ Impact on Ground-Nesting Birds

Where Have All the Quail Gone?

Managing Bobwhite Quail in South Texas

Habitat Restoration and Monitoring

|

B-6172 Habitat Monitoring for Quail on Texas Rangelands By: James Cathey, Robert Lyons, Byron Wright |

|

SP-469 Native Grassland Restoration in the Middle Trinity River Basin By: Kyle Thigpen, Blake Alldredge, Jay Whiteside, Shawn Locke, Larry Redmon, Megan Clayton, James Cathey |

|

WF-001 Native Grassland Monitoring and Management By: Blake Alldredge, Larry Redmon, Megan Clayton, James Cathey |

|

SP-392 Habitat Restoration in the Middle Trinity River Basin By: James Cathey, Shawn Locke, Amy Snelgrove, Kevin Skow, Todd Snelgrove |

General Wildlife Management

EB-6146 Predator Control as a Tool in Wildlife Management

By: Dale Rollins

Integrated Predation Management for Quail Managers- TWA 2-14 By: Dale Rollins

ESP-377 Wildlife Management and Property Valuation in Texas

WF-076 After the Conservation Reserve Program: Land Management with Wildlife in Mind

WF-077 After the Conservation Reserve Program: Economic Decisions with Wildlife in Mind

B-6182 Harvesting Rainwater for Wildlife

By: James Cathey, Russell Persyn, Dana Porter, Monty Dozier, Michael Mecke, and Billy Kniffen

EAG-006 After the Conservation Reserve Program: Economic Decisions with Farming and Grazing in Mind

WF-063 Procedures for Evaluating Predation on Livestock and Wildlife

For more information about Northern Bobwhite Quail visit:

Texas Natural Resources Server

The Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch

National Bobwhite Conservation Initiative

Richard M. Kleberg, Jr. Center for Quail Research