Waterfowl, including ducks, geese, and swans, are set apart from other fowl by their aquatic habitat needs. According to the 2006 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife Associated Recreation, waterfowl are among North America’s most highly valued and observed natural resources. In Texas, there are three main types of waterfowl: diving ducks, dabbling ducks, and geese. In general, diving ducks (ducks that have trouble walking on land but dive underwater with grace to feed) prefer perennial bodies of water, like lakes, stock tanks, backwater river areas, open bays and marshes having a constant supply of water. In contrast, dabbling ducks (ducks that walk easily on land and feed from the water’s surface to about 10 inches) show greater favor to shallower and more seasonal water supplies.

Common Waterfowl Species of Texas:

Dabbling Ducks:

- American Wigeon

- Blue-winged Teal

- Gadwall

- Green-winged Teal

- Mallard

- Mottled Duck

- Northern Pintail

- Northern Shoveler

- Wood Duck

Diving Ducks:

- Bufflehead

- Canvasback

- Common Merganser

- Hooded Merganser

- Redhead

- Ring-Necked Duck

- Ruddy Duck

- Lesser Scaup

Geese:

- Canada Goose

- Lesser Snow Goose

- Ross’ Goose

- White-Fronted Goose

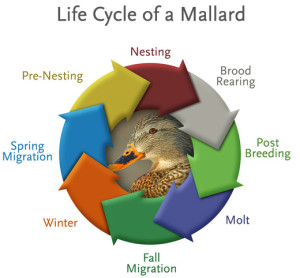

Most waterfowl are migratory. As seasons change, waterfowl populations move to new areas to meet their biological needs. In general, waterfowl typically spend late spring and summer breeding, nesting, and raising young in northern latitudes and during fall and winter move to southern latitudes with warmer climates. This causes national boundaries to be crossed during migration. The extensive migration patterns of North American waterfowl call for special conservation strategies, such as international treaties, flyways, and hunting stamps, to be implemented.

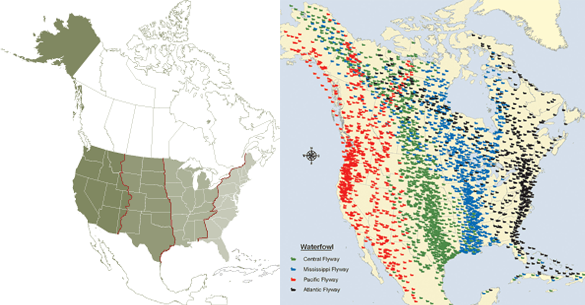

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, signed by the United States, Great Britain (for Canada), the former Soviet Union, Japan, and more recently Mexico, developed conservation practices based on management, science, and public policy that could be applied across national borders for the waterfowl and other migratory birds these countries share. Based on migration flight patterns, four administrative flyways, the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific, were created across the United States; the Central Flyway includes Texas, which holds about 75% of all waterfowl in the Central Flyway based on midwinter population survey estimates. These flyways help determine regulations and management policies based on the traditional migration patterns of each species. Administrative flyways set into place by the United States may be different from the actual biological flyways used by some waterfowl during migration.

Four administrative flyways in the United States (left) compared to biological flyways in North America (right). Some waterfowl may overlap seperate flyways as they move from nesting to wintering grounds. For example, a population from nesting grounds in the Central flyway may overwinter in the the Pacific flyway.

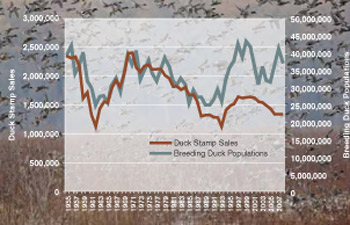

Hunting stamp endorsements paid by hunters generate money for specific groups of game animals in order to help conserve them. In the 1930s, waterfowl populations were drastically declining. The U.S. Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp, known simply as the federal Duck Stamp, was implemented in 1934. Since its inception, over $750 million has been raised with funds going towards research efforts as well as the protection of over 5 million acres of critical waterfowl habitat. The graph below shows that Duck Stamp sales and breeding duck populations are correlated. As populations rise and fall, Duck Stamp sales rise and fall with it. That is until the 1980’s when Duck Stamp sales began declining, indicating that the number of waterfowl hunters are decreasing. This has resulted in a “loss” of $126 million in Duck Stamp revenue between 1995 and 2008, which means less money is available to protect and manage critical wetland habitats.

Duck Stamp sales and breeding duck populations rise and fall together until Duck Stamp sales began to drop in the late 1980s. (Vrtiska et al. 2013. /Wildlife Society Bulletin Vol. 37 No. 2) http://news.wildlife.org/twp/2013-summer/as-waterfowl-hunters-decline/

Physical Attributes

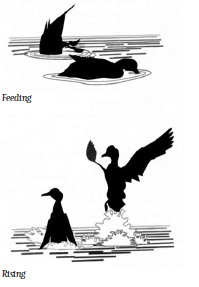

Diagram of Dabbling Ducks feeding and Rising (above)

(adapted from Strickland and Tullos, 2008. Waterfowl Management Handbook for the Lower Mississippi River Valley)

Dabbling ducks feed on aquatic plants and invertebrates on the surface by skimming or just below the surface by dipping their upper body into the water. They have the ability to walk well on land and rise from the water by springing into the air.

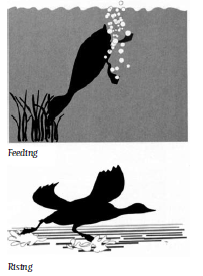

Diagram of Diving Ducks feeding and rising (below)

(adapted from Strickland and Tullos, 2008. Waterfowl Management Handbook for the Lower Mississippi River Valley)

Diving ducks feed on aquatic plants and invertebrates below the surface by diving into the water and swimming more towards the bottom. They do not have the ability to walk well on land and rise from the water by getting a running start and gradually becoming airborne.

Geese are characterized by larger bodies in comparison to ducks but smaller bodies in comparison to swans. Male geese are generally larger in size than females. They eat both land and aquatic plants and occasionally aquatic invertebrates.

Habitat

Most waterfowl like geese, American wigeon, and canvasback are migratory, and in Texas, wintering habitat for migrating waterfowl is intensely managed for some properties. More waterfowl are migratory than not, spending their winters in the warmer south and returning to the north for breeding. Mottled ducks are the only non-migratory dabbling ducks found in the continental United States. Although waterfowl habitat varies, it typically consists of an area with several aquatic areas, such as lakes, ponds, and rivers, within close proximity. Open water (ponds and reservoirs), emergent freshwater wetlands (both coastal and interior), agricultural areas (harvested crop fields), swamps, backwaters, forested wetlands, open bay areas, intertidal marshes, and salt marshes are all utilized by waterfowl in some way.

Dabbling ducks are often associated with large tracts of flooded croplands in greater numbers. Research shows that mallards, one species of dabbling duck, need all of their necessities within a 12-mile radius for survival.

Diet

Dabbling ducks, also called dabblers, like to feed on flooded wetlands, both natural and agricultural, in search of agricultural and natural seeds, native plant parts, and aquatic invertebrates. Examples of agricultural seeds include rice, soybean, corn and milo. Utilizing several different food sources allows waterfowl to obtain all the necessary nutrients. However, some dabblers like the gadwall or American wigeon feed primarily on aquatic vegetation alone.

Diving ducks, or divers, prefer to eat more aquatic invertebrates, plant seeds, and tubers as opposed to agricultural seeds. Some diving ducks like goldeneyes, ruddy ducks or mergansers prefer to eat more animal matter as opposed to canvasbacks, ring-necked ducks, and redheads that prefer to eat mostly aquatic plants.

Geese eating habits are more similar to dabblers than divers. Plant matter such as seeds of wheat, rice, and corn, natural seeds, tubers, green browse, and roots are generally consumed by geese. These geese can be found foraging in harvested croplands, cool-season grass fields, and moist-soil areas. Geese, in comparison to ducks, eat much more land plant matter. However, they do eat aquatic plants.

Waterfowl eat seeds from agricultural pest plants such as red rice. Studies have shown that seeds with thin seed coats generally do not pass through waterfowl digestive systems causing the pest plants’ seeds to be unable to grow. Waterfowl generally eat up to 10% of their body weight in plant matter each day.

| Table 2. Common wetland plant species, their food value, and range of coverage tolerances within wetlands managed for waterfowl. | |||||

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Plant Status | Waterfowl Food Value | Problem | Potential Solution |

| Millet, barnyard grass | Echinocloa spp. | Highly desirable | High | Never | Slow drawdowns mid-season for best results. Disturb soil after 3 seasons, does best the following year after late growing season disking. |

| Annual smartweeds | Polygonum spp. | Highly desirable | High | Never | Early drawdown is essential! Early drawdown of areas that have been deeply flooded for more than one year result in high seed production |

| Threesquare bulrush | Scirpus americanus | Acceptable in moderation | Good | >40% | Keep dry, deep disk, shallow disk, early drawdown, shred, burn |

| Yellow nutsedge | Cyperus esculentus | Acceptable in moderation | Good | Never | Shallow disking early in season promotes |

| Duck potato | Sagittaria latifolia, S. platyphylla | Acceptable in moderation | Good | Never | Never a problem as it is a good food source that typically occurs where other seed producers cannot establish due to moisture conditions. |

| Blunt spikerush | Eleocharis obtusa | Desirable | Good | Never | Disk and shallow flood late summer/early fall will increase this |

| Sprangletop | Leptochloa filiformis, L. fascicularis | Desirable | Good | Never | Typically occurs with desirable, early successional plant communities |

| Dock, sorrel, rumex | Rumex spp. | Acceptable in moderation | Fair | Never | Never a problem as it is typically only a small occurrence within diverse plant community |

| Rushes | Juncus spp. | Acceptable in moderation | Fair | >40% | Shallow disk, early drawdown, deep disk, disk then dry |

| Sedges | Carex spp. | Acceptable in moderation | Fair | >50% | Shallow disk, early drawdown, deep disk, disk then dry |

| Perennial smartweeds | Polygonum spp. | Acceptable in moderation | Fair | >30% | Deep disk or plow followed by flooding and early drawdown in subsequent year |

| Large spikerush | Eleocharis spp. | Acceptable in moderation | Fair | >10% solid block; >25% as scattered patches | Varying hydrologic regime is best, disking, plowing, shredding |

| Toothcup | Ammania coccinea | Desirable | Fair | Never | Typically occurs with desirable, early successional plant communities on moist soil |

| Water primroses | Ludwigia spp. | Acceptable in moderation | Fair | >20% | Alternating water management among years, deep disk then dry, early drawdown, plow |

| Lane, John J. and Kent C. Jensen. 1999. Moist-soil Impoundments for Wetland Wildlife. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Technical Report EL-99-11, 54 p., U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Waterways Experiment Station, Vicksburg, Mississippi. Nelms, K.D., editor and compiler. 2007. Wetland management for waterfowl handbook.USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Greenwood,Mississippi. Strader, Rovert W. and Pat H. Stinson. 2005. Moist-Soil Management Guidelines for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region. Migratory Bird Field Office, Division of Migratory Birds, Southeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Jackson, MS. |

|||||

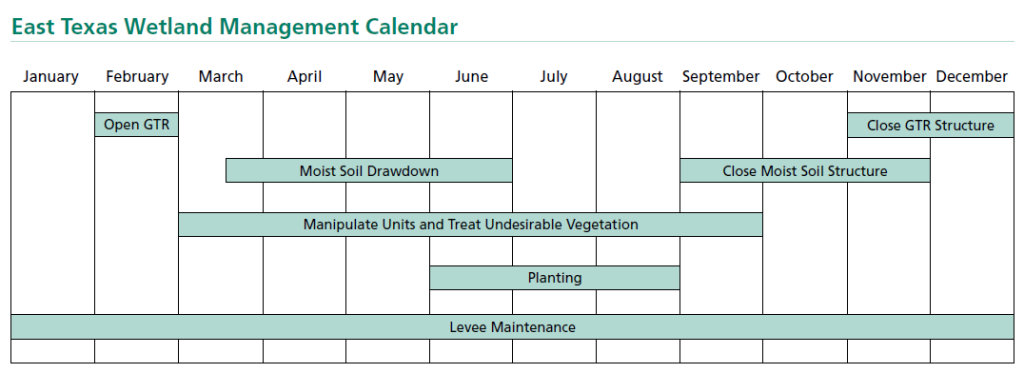

Management

In order to maintain an area for any wildlife including waterfowl, it is best to develop a plan, monitor how the wildlife responds, and keep detailed records of environmental conditions, management treatments and actions, and the responses of the wildlife and plant communities. Planning and documentation will help better understand the needs of an area and help direct management efforts in the correct direction.

Poorly drained areas can be easily transformed into waterfowl wintering habitat and are usually chosen to be developed into such habitats. However, if areas are flooded too frequently or do not drain well enough, many plants can deteriorate or lose nutrition and energy essential to waterfowl especially during molting and reproduction. Several wetland habitats, including livestock ponds, natural wetlands, green tree reservoirs, moist-soil impoundments, and levees, can create ideal waterfowl habitat.

Moist-soil impoundments mimic flooding and drying cycles and can provide many of these essential plants and invertebrates consumed by waterfowl, many having low deterioration rates. Many factors play into creating a perfect moist-soil impoundment such as sunlight, soil temperature, soil moisture, soil pH and nutrients, seed bank and successional stage of the plant community.

Levees can be created to flood an area. Clay soils are best when creating levees, because they tend to seal more quickly if the area is flooded. When maintaining a levee, it is important to check for erosion and woody vegetation encroachment often.

Green tree reservoirs can damage or kill desirable bottomland hardwood trees if flooded up before the first hard freeze or not drawn down after buds begin to swell on trees.

Planting can be used to create a more ideal area for waterfowl. Find which plants will work best for the target waterfowl and plant accordingly. However, if hunting will occur, first check baiting laws prior to growing crops in wetland areas.

Conservation

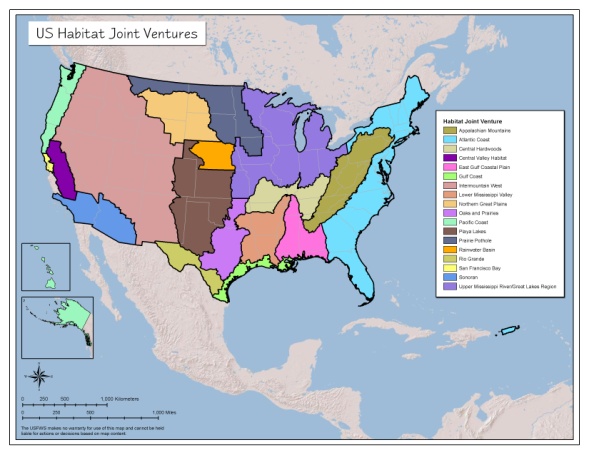

In order to maintain waterfowl populations, international management will benefit the most, because most waterfowl are migratory. In the 1980s, suitable nesting cover and brood habitat decreased resulting in the plummet of waterfowl populations. Action was taken by the United States, Canadian, and Mexican governments in order to develop an international management plan called the North American Wildlife Management Plan (NAWMP) that has been a guiding force in habitat management and wetland policy for over twenty five years.

The NAWMP works through Joint Ventures (JV) or regional partnerships of organizations dedicated to a common goal of management and conservation of birds. Organizations such as Ducks Unlimited, Delta waterfowl, businesses, universities, volunteers, donors, and landowners work together on key management areas in order to better maintain land. $7.5 billion has been invested to benefit more than 22 million acres of affected habitat since the inception of NAWMP and the JVs. The JVs now cover the entire US and Canada with 5 separate JVs being represented in Texas alone. The five in Texas support waterfowl to upland game birds and other grassland birds.

Citations

“Flyways.us.” Home. USFWS, n.d. Web. 14 April. 2014.

North American Waterfowl Management Plan [NAWMP] Plan Committee. 2012. People Conserving Waterfowl and Wetlands. Canadian Wildlife Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Washington, D.C., USA.

“Fws.gov/birdhabitat/JointVentures” Home. USFWS, n.d. Web. 14 April. 2014.

“Ducks.org” Home. Ducks Unlimited, n.d. Web 14 April. 2014.

Land, John J. and Kent C. Jensen. 1999. Moist-soil Impoundments for Wetland wildlife. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Technical Report EL-99-11, 54 p., U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Waterways Experiment Station, Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Cross, D. H. 1988. Waterfowl management handbook. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. Fish and Wildlife Leaflet 13. Washington, DC.

Nelms, K.D., editor and compiler. 2007. Wetland management for waterfowl handbook. USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Greenwood, Mississippi.

Strader, Robert W. and Pat H. Stinson. 2005. Moist-Soil Management Guidelines for the U.S. Fish and Widllife Service Southeast Region. Migratory Bird Field Office, Division of Migratory Birds, Southeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Jackson, Mississippi.

Strickland, B. K. and A. Tullos, editor and compiler. 2008. Wetland Management for Waterfowl Handbook for the Lower Mississippi River Valley. Mississippi State University Extension Service, Mississippi State, Mississippi.

http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/publications/pwdpubs/media/pwd_pr_w7000_1179a.pdf

Suggested Readings

Techniques for Wetland Construction and Management

Texas Waterfowl from Texas A&M University Press

Webinar: Wetlands Management for Attracting Waterfowl

For more information

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Waterfowl Conservation Partners:

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

- Ducks Unlimited

- Delta Waterfowl

- US Fish and Wildlife Service

- Texas Wildlife Association