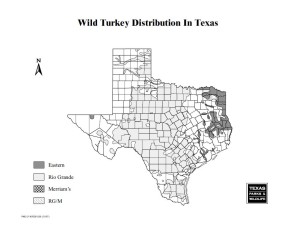

The Rio Grande wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo intermedia) has the largest population and the widest range of the three turkey subspecies (Rio Grande, Merriam’s, and Eastern wild turkeys) found in Texas. Unregulated hunting in the 1800s greatly reduced the Rio Grande wild turkey (RGWT) population in Texas to about 100,000 birds by 1920. Since then, their numbers have recovered thanks to better habitat management, restocking programs by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), and partnerships with landowners and conservation groups. However, there has been a steady decline in their populations in certain regions since the 1970s, which prompted TPWD to partner with universities to study the biology and habitat requirements of the turkeys in different parts of the states.

The Rio Grande wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo intermedia) has the largest population and the widest range of the three turkey subspecies (Rio Grande, Merriam’s, and Eastern wild turkeys) found in Texas. Unregulated hunting in the 1800s greatly reduced the Rio Grande wild turkey (RGWT) population in Texas to about 100,000 birds by 1920. Since then, their numbers have recovered thanks to better habitat management, restocking programs by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), and partnerships with landowners and conservation groups. However, there has been a steady decline in their populations in certain regions since the 1970s, which prompted TPWD to partner with universities to study the biology and habitat requirements of the turkeys in different parts of the states.

The RGWT do not occupy the Trans Pecos and High Plains ecoregions of Texas. Typically, they inhabit areas that receive enough rainfall to sustain their food sources. The Edwards Plateau is their historic geographic center and has the highest number of RGWT today. Male turkeys are referred to as “toms”; males of breeding age are “gobblers”; females are “hens”; juveniles are “poults.”

Physical Attributes

The bodies of wild turkeys are covered with 5,000 to 6,000 feathers. These feathers provide insulation, lift during flight, and touch sensation and ornamentation. A wild turkey undergoes five molts (feather replacement) during its lifetime: natal, juvenile, first basic, alternate (first winter), and basic (adult plumage). The body feathers of toms are vibrantly colored: iridescent copper, bronze, red, green, and gold. While hens have these same colors, they are significantly dulled and muted which causes the female to appear brown. Gobblers have a beard, which is a cluster of long follicles in the center of their chest that can be an inch to 10 inches long. Unlike the rest of the body feathers which undergo 5 molts throughout an RGWT’s lifetime, the beard does not molt. It becomes visible when the turkey is 6-7 months of age, and it continues to grow throughout their lifetime. Hens may occasionally have beards, although this uncommon event produces much shorter beards than toms. Both toms and hens have sparsely feathered heads with bare legs and feet that are pink to red in color. Toms grow a spur on the lower third of their leg that starts off small and rounded, but which becomes pointed and about 2 inches long with time. Hens also have a spur, although their spurs stay small and blunted. Gobblers weigh 17-21 pounds and attain a height of 40 inches. Hens weigh 8-11 pounds and are 30 inches tall. Poults are relatively small when hatched; they only weigh 2 ounces.

Mating and nesting

Gobblers attract a hen’s attention by gobbling and strutting. The hen will select a mate by lying close to the ground in front of him, which signals the male to begin copulation. Nesting begins in early spring in south Texas and continues on through July and August in central and north Texas. Hens choose nesting sites that are in grass clumps, brush piles, understory brush, or leaf litter.

They scratch out a shallow depression or bowl shape in these selected areas to form the nest. In order to protect their nests, hens choose sites that have enough herbaceous cover to hide the poults while still allowing the hen an unobstructed view to watch for threats. Nest sites are typically found in areas that are within ¼ mile of a water source, have grass heights of 18 inches, and have a high abundance of insects. Females lay one egg per day, producing an average total of 10-11 eggs. The eggs are cream or tan in color and may have brown speckles. Incubation lasts around 28 days after the last egg is laid. After hatching, the hens and poults form a brood; this brood forages together for the majority of the day. At this young age, poults mainly consume invertebrates such as grasshoppers, beetles, and spiders. The poults continue to roost on the ground for the first two weeks of life until their natal plumage is replaced by flight feathers and they can fly up into roost trees.

Habitat and diet

The Rio Grande wild turkey is an opportunistic forager that feeds on green foliage, insects, seeds from grasses and forbs, and mast (acorns and nuts). Annually, their diet consists of about 36% grasses, 29% insects, 19% mast, and 16% forbs. The individual plant species that a turkey uses as food varies by region and by season. Water is very important to RGWTs; this includes surface water, metabolic water, and preformed water. Surface water is free-standing water such as ponds, creeks, or troughs. Metabolic water is derived from foods when they are digested. Preformed water is contained within the food itself, such as the water found in succulent plants.

RGWTs require a habitat that contains an interspersion of wooded and open areas. A mix of these areas, while individually important to the turkeys, also provides the added benefit of large amounts of edge habitat. Edge habitat is useful for escaping from both predators and the heat. Although RGWTs do not migrate, they have two distinct roosting sites: summer roosts and winter roosts. They prefer to roost in tall hardwood trees that have broad canopies with many horizontal limbs. Species such as live oak, hackberry, pecan, elm, and cottonwood exhibit these traits. In areas that lack trees, artificial roosts can provide similar benefits. RGWTs prefer to roost over an open understory, which is why they can often be seen roosting over water. Roosting areas consist of 10-15 acres with a 50-70% canopy cover. An important part of the roosting area is the area that surrounds it; turkeys need open spaces within 100 yards of roost trees to serve as launching and landing pads for ascending and descending from the roosts. In general, these highly mobile birds need large amounts of usable space, as they annually travel between 6 and 26 miles. For example, their range in the Rolling Plains varies between 2,400 and 5,900 acres, whereas their range in the Edwards Plateau varies from 3,800 to 6,600 acres. In the spring, bred hens move independently from hens that did not breed. In the summer, gobblers separate from juvenile males and non-breeding females. In the late summer, brood flocks form. In the winter, the males join the flocks.

Predation and other mortality factors

Because hens nest on the ground, the reproductive success of RGWTs depends on weather and yearly rainfall, the range condition, and the body condition of the individual hen. In addition to these factors, there are many predators that prey on the nests and hens. The most common of these nest predators are raccoons and foxes although reptiles, owls, hawks, skunks, feral hogs, and other mammals will also prey on the hens, eggs, and poults. Several different predators may depredate the same nest, but they do not always consume the entire clutch of eggs. In some instances, hens may resume incubating the surviving eggs after depredation of the nest. Life does not get much easier for poults after hatching, as many of the same species that prey on nests also prey on poults. On average, there is a 60-75% nest failure and a 12-50% poult survival rate annually. Survival increases once they begin roosting in trees rather than on the ground.

Wild turkeys are susceptible to a number of diseases. These diseases include ones that are common among domestic poultry, such as mycoplasmosis, salmonellosis, aspergillosis, and reticuloendothelosis, which affect the immune system and causes abnormal internal growth. The avian pox causes lesions which prevents the affected turkey from foraging and makes them more prone to predation.

Conservation and management

The decline of RGWTs in certain parts of their range may be due to these predation and mortality factors, in addition to changes in land use, land fragmentation, and an increase in brush height/density. Interested landowners and land managers can manage their land for turkey in multiple ways: preventing cattle from overgrazing, conducting prescribed burns, and practicing brush control, among others. Ensuring sufficient nesting and brooding habitat will increase nesting success and poult survival resulting in more individuals being recruited into the population, and maintaining roost sites will enhance the usability of the land even more.

For more information about the biology and habitat requirement of RGWT and general recommendations for landowners to implement, see the publications that AgriLife has developed below.

Rio Grande Wild Turkey in Texas: Biology and Management (EB-6198)

Habitat Appraisal Guide for Rio Grande Wild Turkey (ESP-317)

Habitat Appraisal Guide for Rio Grande Wild Turkey (ESP-317)

Managing Brush Near Rio Grande Wild Turkey Roosts (WF-047)

Managing Brush Near Rio Grande Wild Turkey Roosts (WF-047)

Guide to Abundance Estimation Techniques for Rio Grande Wild Turkey (WF-050)

Guide to Abundance Estimation Techniques for Rio Grande Wild Turkey (WF-050)

Rio Grande Wild Turkey Life History and Management Calendar (WF-074)

Rio Grande Wild Turkey Life History and Management Calendar (WF-074)

Webinar:

Rio Grande Wild Turkey Biology and Management

Additional Resources: